What must be done after a national dialogue to revamp the country’s ailing film industry hits a snag because of one thing – language?

Once upon a time, a group of people in the Bible, united in thought and ambition were set to build a tower to reach the heavens, aiming to make a name for themselves – and they were on course. They called it the Tower of Babel. But after God observed their powerful unity and the pride behind their ambition, he thwarted their plans with a single stroke – confused their languages, preventing them from understanding each other. That was the end of the tower project as we know it. Just language.

Like the people working on the Tower of Babel, the National Film Authority assembled Ghana’s biggest movie stars and creatives to reimagine the once booming local film industry. The sector, which provides billions of dollars in revenue and hundreds of thousands of jobs in other countries, appears to be slowly dying off in Ghana.

It will seem that locally, the sun is setting on a golden generation of actors and producers who graced the silver screens with their talents, educating, entertaining and influencing the entire nation for decades. Why is this happening? Clearly, the dynamics in the industry, right from production, through promotion have changed significantly and we’re yet to catch up.

But I’m not an actor or a movie producer so I’ll defer to the real industry people – the film makers and creatives who were assembled by the NFA for the national film dialogue at the University of Ghana. This meeting was crucial and timely. The only problem, a big one, is that many of the people who attended, especially those from the kumawood space struggled to understand the discussions.

It was not for the lack of technical knowledge, or the shortage of expertise in the field. It was because of the language of the day; English. As a journalist and communications specialist, I have come to learn that audience understanding is more crucial to any conversation than even the quality of material being delivered.

I could produce the best film ever made in English, but if I put it before a Russian audience with limited English proficiency, without providing a means for them to understand, everything said will be noise. Just noise. So, it’s no surprise that Kwadwo Nkansah (Lilwin), one of the most active actors and producers, had a cause to complain about the entire session being in English. Like the Russians watching my imaginary English film without subtitles, the entire discussion albeit crucial and timely, was just noise!

The Board Chairman of the NFA, Ivan Quashigah, has since downplayed the concerns in an interview, as they “take us away from the objective.” But Mr. Quashigah, himself an accomplished filmmaker, famed for producing and directing the award-winning television series Things We Do for Love and more recently YOLO, surely knows this is not as trivial as he sets it out to be.

In the interview on Hitz FM with Doreen Avio and Kwame Dadzie, Mr. Quashigah insisted, as a way of justifying his response, that nobody was prevented from speaking their local dialect. But his attempt to defend what I can only refer to as a ridiculous blunder on the part of the NFA, further strengthened the point of LilWin.

If you decide to hold an event on the 8th floor of a building without an elevator or step-free access, you have automatically excluded wheelchair users. And merely saying no one was prevented from attending does very little to explain away the situation.

Worse, Mr. Quashigah said, “when he [Lilwin] spoke in Twi, I didn’t understand. I’m a Ewe and I doubt if I spoke Ewe he would even try to understand.”

What is the point in inviting someone for a dialogue if you can’t understand him and he can’t understand you too?

Is it not true, that indeed, many Kumawood stars struggle to understand and express themselves in English? Some of them speak and write fluent English, but there are also those who cannot. So, as a national body tasked with harnessing talents and ideas of big film stars, the focus should be how to get through to them and receive from them.

Lilwin saying he couldn’t understand the English and calling for Twi is just like a hearing-impaired person calling for sign language. Will it matter that Ivan Quashigah isn’t deaf and doesn’t sign, if that request is made?

Lilwin’s concern was that most of these dialogues favour English over other local languages which people are more fluent in. But he meant to say, I surmise, that he feels excluded because he cannot speak or understand English. And that’s a legitimate concern.

Unlike the story of the Tower of Babel where the builders had no access to interpretation, subtitles and whatnot, the NFA knows the problem and also knows the solution.

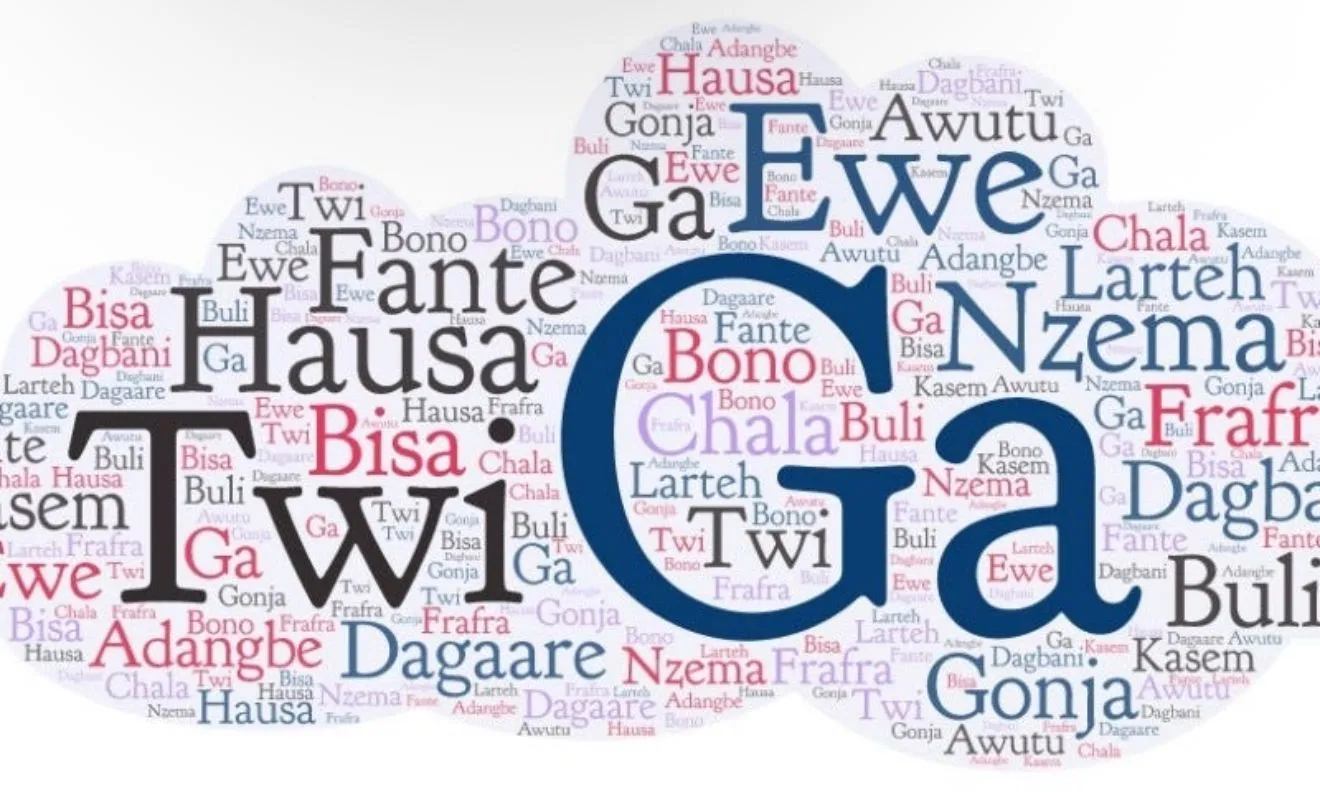

This is less about Ivan Quashigah and the NFA, and more about how inaccessible and exclusionary the Ghanaian society is set up to be – especially for fellow Ghanaians. That same dialogue, if it featured foreign nationals, would have seen French, Spanish, Chinese, German and other interpreters employed to ensure seamless communication. So why draw the line when people ask for Twi, or Ga, or Ewe?

This speaks to a deeper level of institutionalised linguistic racism and discrimination which should not be countenanced.

And this is not about getting interpreters for every attendee. At the point of invitation and registration, organisers are supposed to understand the linguistic capabilities of their audience and based on that, decide whether they should hire and how many interpreters they’d need for a successful programme.

In more ways than one, people’s talents, skills and abilities are sidelined because we refuse to engage these abilities. English is obviously our official language in Ghana. So, the point is not about dropping English in favour of Twi or Ga or Dagbaani. It is about recognising that people have more to offer once the barrier of language is lifted.

I cannot overemphasise that people are differently abled and to harness everyone’s abilities, we need to begin thinking about accessibility and inclusion as key considerations for our national development programming. This does not “take us away from the main issues”, it is the vehicle through which the issues can be solved.